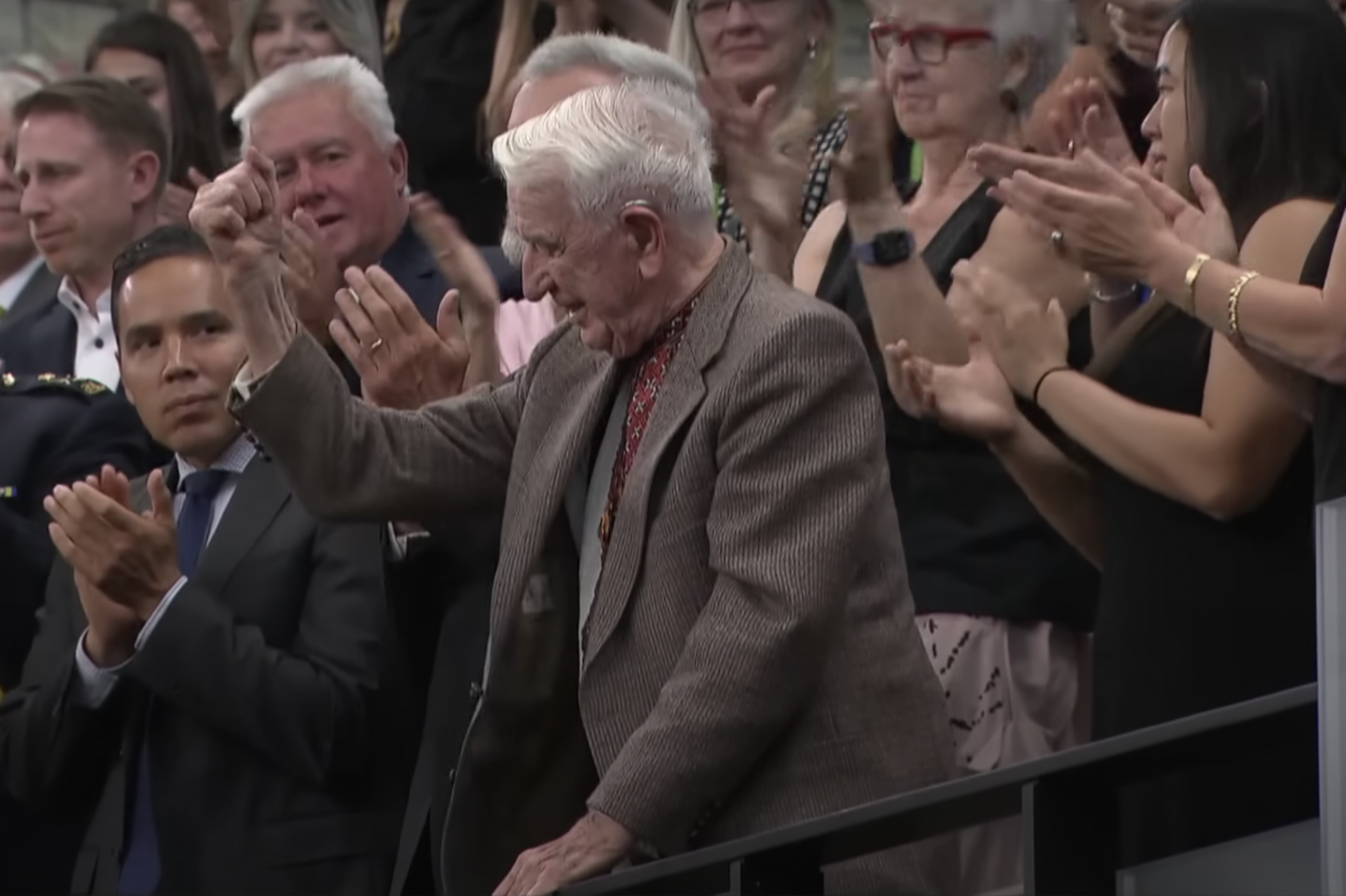

Yaroslav Hunka, the Waffen SS veteran honoured by the Canadian Parliament as a “hero” last September, was recently awarded a medal named after a Ukrainian Nazi collaborator.

The award was presented by a regional official who is a member of a modern day far-right political party in Ukraine.

The Yaroslav Stetsko medal, whose official title can be translated to the “honorary award of the Ternopil Regional Council for services to the Ternopil Region,” was presented by Oleh Syrotyuk to Hunka’s great-niece, Olga Vitkovska, on March 19, Hunka’s 99th birthday.

Hunka’s commendation was brought to attention by Ukrainian-Canadian political scientist and University of Ottawa professor Ivan Katchanovski.

Ukrainian state broadcaster Suspilni Novyny reported that the ceremony took place in the Western Ukrainian city of Ternopil, and that the regional council approved the award on February 6.

According to Katchanovski, Syrotyuk is the head of the Ternopil Regional Council’s standing commission on legal affairs and the former governor of the Ternopil Oblast. He is also the local leader of the far-right Svoboda Party.

The Svoboda Party has its roots in Ukraine’s neo-Nazi movement, and venerates wartime Nazi collaborators like Stetsko.

Originally from Ternopil, Stetsko was a virulently antisemitic Ukrainian ultranationalist who, along with Stepan Bandera, was one of the leaders of the militant and collaborationist Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B).

Bandera’s faction supported the creation of the Ukrainian National Government on June 22, 1941, the day Nazi forces began their invasion of the Soviet Union, unleashing the first phase of the Holocaust in the region. It was Stetsko who announced the creation of a collaborationist Ukrainian state in Lviv eight days later.

“Stetsko was the ideologue of the OUN-B and self-proclaimed Prime Minister of their aborted, June 30, 1941 state,” said Per Anders Rudling, a historian at Lund University and an expert on nationalism and ideological history in the post-Soviet successor states and their overseas diasporas.

“He was one of the most radical of the OUN-B activists, endorsing the extermination of the Jews, and eugenic engineering, among other things.”

Rudling detailed Stetsko’s fervent antisemitism and thoughts on eugenics in the context of the radical Ukrainian nationalist tradition in a 2019 article in the journal Science In Context.

Katchanovski told The Maple that the Stetsko Medal is, regionally speaking, akin to receiving an award from the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

The medal was awarded for Hunka’s “significant personal contribution to the provision of assistance to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, active charity and public activity.”

State broadcaster Suspilni Novyny indicated Hunka was concerned he would be extradited after the scandal in Parliament last fall and fled to an undisclosed location in Latin America in late 2023. He has since returned to Canada, according to the report.

Scandal Reverberates

After Hunka received a standing ovation in Parliament during Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s visit to Ottawa, journalists discovered Hunka’s fond online recollections of his time volunteering for the 14th Waffen-SS “Galicia” Division.

The episode prompted widespread outrage, as well as commentaries defending those who volunteered to fight with the SS division during the Second World War.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau initially denied having any knowledge of Hunka or his invitation to Parliament, and Anthony Rota took responsibility for the incident by resigning from his position as house speaker.

But new reports this year revealed that Trudeau invited Hunka to attend a Zelenskyy rally in Toronto, an invitation made at the request of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC).

The UCC has long been alleged to represent Ukrainian ultranationalists, a political section that includes devotees of wartime Nazi collaborators like Stetsko and Bandera.

According to Katchanovski, Stetsko stated his Ukrainian government would closely cooperate with the Nazis, including in the elimination of the local Jewish population. In his Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State, Stetsko vowed to “work closely with National-Socialist Greater Germany under the leadership of Adolf Hitler.”

Forty-two years later in 1983, Stetsko, by then leader of the “Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations,” was warmly received at the White House by then U.S. president Ronald Reagan as the “last premier of a free Ukrainian state.”

“Stetsko expressed his support for Nazi ‘methods of exterminating Jewry’ to the Germans in July of 1941,” said Katchanovski.

“This occurred after the Bandera faction of the OUN and other OUN-led militias organized large-scale pogroms in Lviv and many other locations in Western Ukraine.”

Several thousand Jews were massacred by Ukrainian ultranationalists during the Lviv Pogrom of 1941.

Lev Golinkin reported for The Forward in 2021 that Stetsko and Bandera, along with other Nazi collaborators and SS volunteers, continue to be well commemorated throughout Western Ukraine.

“There are many monuments and streets named after Nazi collaborators from the OUN and the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) and the SS Galicia Division in the Ternopil Region,” said Katchanovski.

The OUN, UPA and SS Galicia were all directly complicit in war crimes during the Second World War, including the Holocaust. They were also responsible for the mass murder and ethnic cleansing of as many as 100,000 Poles, as well as Jews, Russians, Belarusians, other Ukrainians and other minority groups in the region.

The Galicia Division, Hunka’s old unit, was controversially determined to not be responsible for war crimes by Canadian justice Jules Deschênes when he was tasked by the Mulroney government in the 1980s to investigate allegations that war criminals were living in Canada.

Deschênes’ decision opposed established international criminal precedent dating back to the post-war Nuremberg trials, which had determined the entirety of the SS to be a criminal organization that was collectively responsible for the Holocaust.

The exact number of SS veterans, Nazi collaborators and other assorted fascists accused of war crimes who found refuge in Canada after the Second World War is still unknown, as much of the Deschênes Commission’s final report remains secret.

Taylor C. Noakes is an independent journalist and public historian from Montreal.

Member discussion